Creating a compelling and informative speech is an art in itself. However, what if you need to make it longer? Don’t worry, we will try to explain how to make a speech longer. Whether you’re trying to meet a specific need in terms of duration or want to add more depth to your topic, this guide will help you extend your speech. We’ll also touch on how to make your presentation longer, as both skills often go hand in hand.

How to Make a Speech Longer: Practical Advice

Know your target length

How to make speech longer? Before diving into the strategies for extending your speech, it’s crucial to understand the length required. Your audience’s expectations and the context of your presentation will determine how long your speech should be. Here are some common time frames for speeches:

- 2-minute speech: Often used for short introductions or brief statements

- 4-minute speech: Suitable for concise explanations or pitches

- 12-minute speech: Typical for classroom presentations and some business contexts

Effective strategies for lengthening your speech

How to make your speech longer? The process involves using strategies like research, real-life examples, and talking with the audience.

- Research and gather information. Collect more information on your topic. Extensive research can provide more content for your speech. Use academic sources, articles, books, and online resources.

- Add supporting points. Expand your main ideas with extra supporting points. This can help provide more than enough for your audience to gain an understanding of the topic.

- Include real-life examples. Relate your topic to real-life situations or experiences. Personal anecdotes or case studies can make your speech more engaging and informative.

- Incorporate data and statistics. Use data and statistics to support your claims. Numbers and figures can add depth and credibility to your speech.

- Use visual aids. Consider adding visual elements to your presentation. Infographics, charts, and images can fill time and enhance the audience’s understanding.

How to Make Your Speech Longer: Tips and Strategies for Extending Your Presentation’s Length

How to make speeches longer? Ensuring that you reach the required limit can be daunting when faced with the challenge of delivering a presentation. While we’ve already discussed various strategies for extending speeches, this section offers insights on how to make a presentation longer. Here, we’ll explore new tips and techniques to help you lengthen your speech.

- Explain concepts in detail. Instead of skimming over topics, investigate them. Give detailed explanations, examples, and comparisons.

- Introduce quotations and citations. Include quotations from experts in the field. Citing reliable sources gives your speech more credibility and a greater length.

- Use transitional phrases. Use phrases like “Moving on,” “Another key point,” or “Now, let’s discuss” to guide your audience through your speech, giving the impression of a more extended presentation.

- Include personal insights. Give your perspectives and demonstrate your understanding of the subject. Describe the connection between it and your life events or convictions.

- Analyze counterarguments. Talk about and then disprove any counterarguments. In doing so, you explore the subject more fully and give your speech greater depth.

How long is this speech?

“How long is this speech?” is a common question for anyone preparing to present. The actual length of a speech can vary depending on the speaking pace and content. To determine the exact duration of a speech, it’s best to practice and time yourself. You can use various tools, like a stopwatch or timer, to measure the duration.

Here are some general guidelines for different speech lengths:

- How long is a 2 minute speech? A 2-minute speech consists of approximately 200 to 250 words.

- How long is a 4 minute speech? A 4-minute speech usually contains around 400 to 500 words.

- How long is a 10 minute speech? A 10-minute speech generally comprises 1,000 to 1,250 words.

The length of your speech may vary depending on your delivery style and the intricacy of the subject, so keep in mind that these are only estimated word counts. Making sure your speech is of the appropriate duration requires practice.

Recommended reads

How to Make a Presentation Longer: Expanding Your Slides

How to make presentation longer? A lengthy and engaging presentation may often be essential to effectively communicating your message. Expanding your slides is one way to extend the duration of your presentation. This guide will explore strategies and techniques to help you make a presentation longer without sacrificing quality or engagement. Here are some presentation tips for you:

- Use multiple slides per point

One of the simplest ways to make a presentation longer is to create many slides for each key point. Each slide can focus on a different aspect or sub-point. This approach adds to the duration and makes your presentation more visually engaging.

- Interactive exercises

Incorporate interactive exercises or quizzes (for example, with a video) to engage your audience. Create slides that guide them through these activities and discuss the results or insights gained.

- Exploring ethical considerations

Discuss the ethical aspects of your topic and explore different viewpoints. Create powtoon slides highlighting the ethical dilemmas or considerations associated with your subject matter.

- Future implications

Talk about the trends and implications of your issue for the future on separate slides. Discuss what possibilities you see for the future and urge the audience to consider the options.

By implementing these strategies and expanding your slides, you can create a longer, more engaging, and right presentation that effectively conveys your message while you keep your audience attentive and informed. Balancing length with quality is the key to a successful extended presentation.

If possible, you should aim for two goals simultaneously. The first is to make your speech an appropriate length. The second is to fill it with relevant, engaging, and educating content. You will never deliver a good presentation if your only goal is to talk about something for 5 minutes.

Choosing the right presentation maker can significantly impact your success in extending your presentation. There are several reasons to consider employing a presentation maker in your speech development. These tools often offer many features, such as templates, animation, and collaboration options, making the creation of engaging and dynamic presentations easier. However, selecting the proper presentation maker is crucial. There are differences across presentation makers; therefore, it’s important to match your selection to your speech’s demands and objectives.

How many words is a 12-minute speech?

How many words is a 12 minute speech? The number of words in a 12-minute speech can vary based on factors like your speaking pace and the complexity of the content. A 12-minute speech typically consists of approximately 1,500 to 1,800 words. To calculate the precise word count for your speech, consider the following:

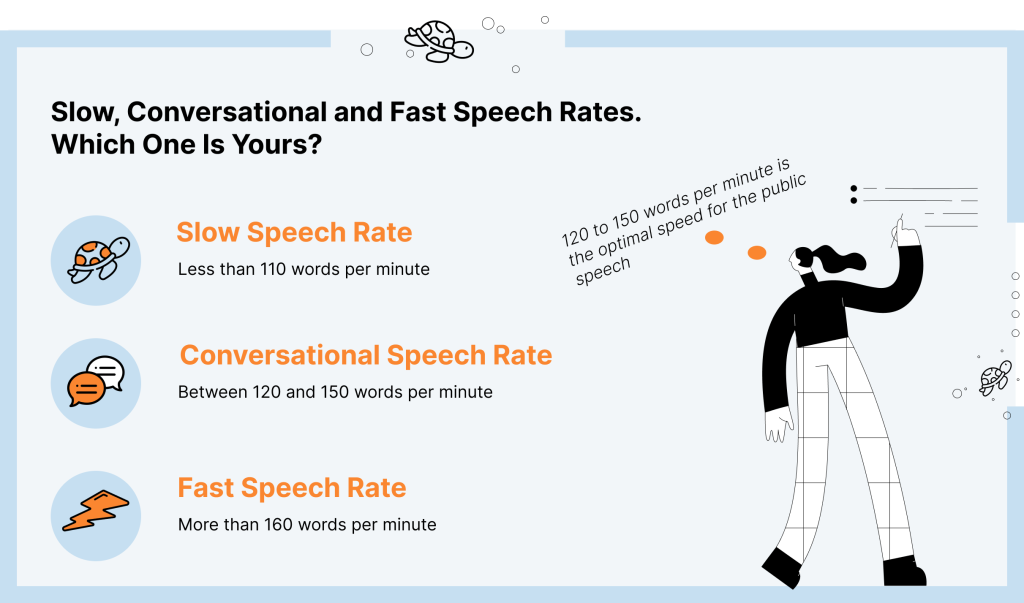

- Speaking pace. Your speaking pace will impact the word count. A slower pace may need fewer words to fill 12 minutes, while a faster pace will require more words.

- Pauses and emphasis. Watch your breaks and concentrate on some points. The components mentioned might also influence the duration of your delivery.

- Audience engagement. Making your speech more intriguing by involving the audience in activities and discussions might prolong your speech. To make your presentation more exciting, ask audience members to share their ideas and questions while you’re speaking.

Remember that practicing and timing your speech is crucial to ensuring that it fits within the desired 12-minute timeframe.

Utilizing the CustomWritings.com Words-to-Time Converter

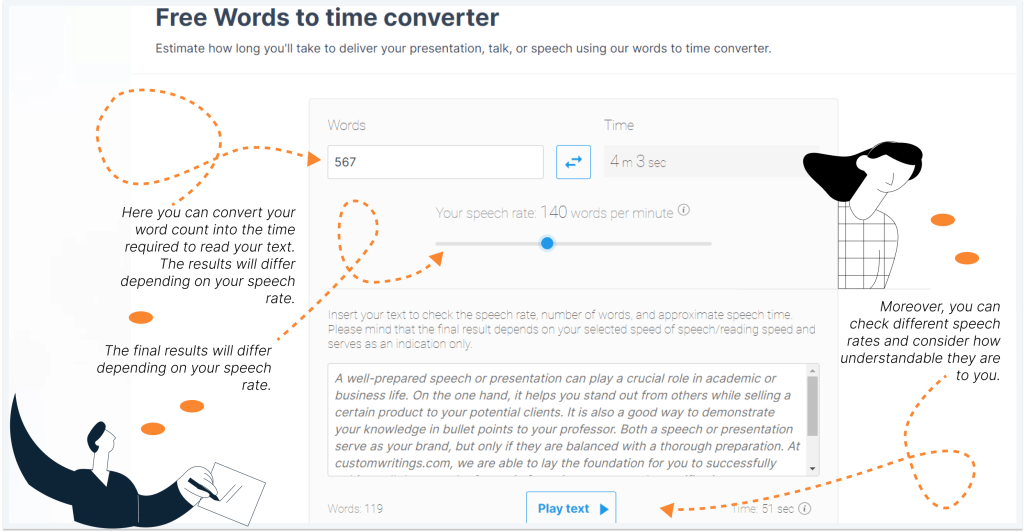

If you want to prolong your presentation or speech, you must have tools to manage your time and ensure that your content matches the given duration. It is in this regard that the CustomWritings.com Words to Time Converter maker will serve as an invaluable tool. Using this online tool, one may calculate the length of the presentation depending on the word count. Here’s how it works:

- Words. You enter the word count of the speech, presentation, or any written material you plan to deliver.

- Time. You can indicate the specific time you need to deliver your speech.

- Your speech rate. Here, you will enter your speaking rate in terms of words per minute. The tool then approximates the speech time depending on the word count and your stated speaking rate.

This tool ensures that your speech fits within the desired time frame. It can be particularly helpful when making your presentation longer or shorter, as it indicates how many words are necessary to meet your time goal.

The art of extending a speech while maintaining its quality is a valuable skill. Whether you’re striving to meet specific time requirements or aiming to provide more depth to your topic, this guide has provided essential insights into how to make a speech longer and more effective. With these techniques and tools at your disposal, you can make a presentation or speech longer, ensuring that it meets the required duration while captivating and informing your audience.