Creative writing is a type of writing in which you put creativity at the forefront and set it as your goal. Through the use of imagination, creativity, and innovation, you can tell the story in the best possible way, using strong written visuals to reinforce the emotional impact on readers, such as in writing poetry, writing short stories, novels, and the like. As better this work is done as more money you can get for your effort as an author.

This type of writing is something completely opposite to academic writing or journalistic writing. There are many types of creative writing that will carry different moods. Creative writing uses feelings and emotions to create a strong visual image in the reader’s mind, while other forms of writing usually leave the reader with only facts and information, rather than emotional intrigue. Whether it be a series of autobiography books or a standalone installation, the factors that determine creative writing have more to do with how it is artistically perceived by the reader.

If you’re a writer looking to get better or go pro, you need to understand the importance of continuous learning and structure. Creative writing is all about storytelling and emotional impact, but students are often juggling multiple academic commitments like dissertations or thesis projects. For those tackling big writing projects, a dissertation writing service is a lifesaver. These services will help you with research, content refinement and academic standards so you can focus on your creative dreams while still achieving academic success.

Whether you’re pursuing an MFA or just trying to balance creative and academic writing, professional support means you don’t have to sacrifice quality. By outsourcing technical writing to experienced professionals you can spend more time writing imaginative stories, poems or scripts that really connect with readers.

What Are the Elements of Creative Writing?

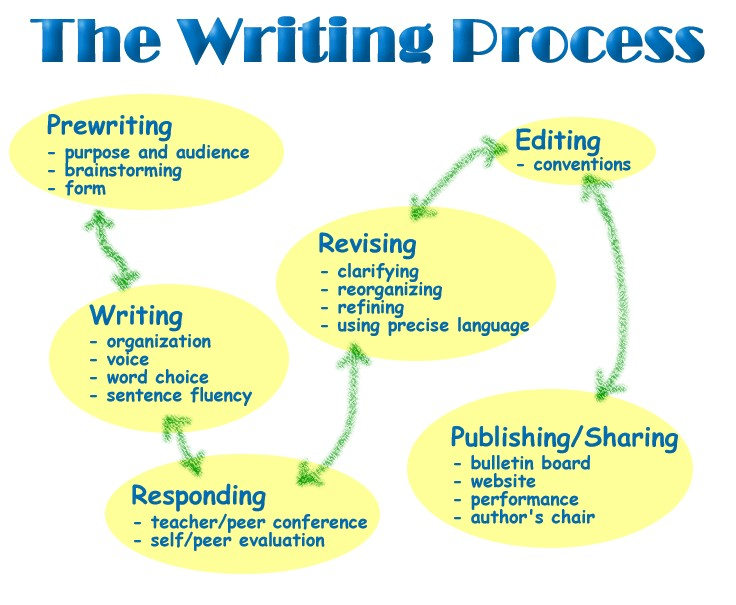

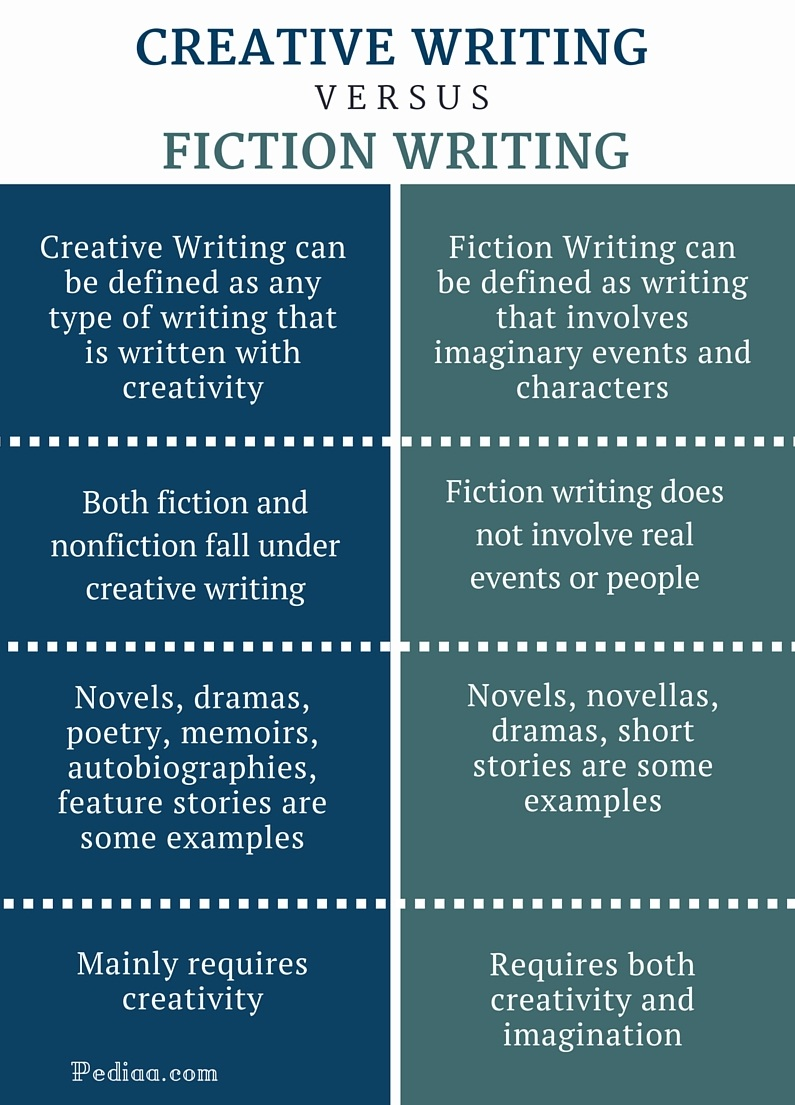

To get better at creative writing, you need to understand the elements of what makes writing a great paper. You can’t build a car engine without understanding what role each part plays, so writing it is the same. Here are the elements that make up creative writing and why each is just as important as the other. These elements make the difference between creative writing and, for example, fiction writing.

To inspire you to write your creative paper and learn how to choose the most interesting topic for your work, then look at the examples of other writers and check them through:

Creative Writing Topics & Ideas

Library rules and regulations no one told you about

How to turn stress into motivation using paper: a guide for “negative thinkers”

Unique Plot

What most distinguishes creative writing from other forms of writing is the fact that the former always has some kind of plot—and a unique one. Remakes are also considered to be creative writing, however, most creative writers create their own stories, shaped by their own unique ideas. Without a plot, there is no story.

Note! And without a story, you just write down the facts on paper, like a journalist or scientist. Learn how to build your paper, and you’ll open the ability to write at a higher level without having to search for your story.

Character Development

Characters are essential for creative writing. While you can certainly write a book creatively using a second-person perspective (which will be covered below), you still need to develop a character to tell the story.

Character development can be defined as discovering who has the main role and how it changes throughout the story. From start to finish, readers should be able to deeply understand your main characters.

Main Theme

Almost every story has a main theme or message, even if the author doesn’t necessarily want it. But creative writing needs that subject or message to be complete. This is part of the beauty of this art form. By telling a story, you can also teach lessons.

Visual Descriptions

When you read a newspaper, you don’t often read paragraphs describing neighborhoods where events took place. Visual descriptions are mostly reserved for creative writing. You need them to help the reader understand what the characters’ environment looks like. Show, not tell, that the paperwork engages readers and allows them to put themselves in the characters’ shoes—that’s why people read.

Point of View

There are several people from which you can write. At the same time, two of them are most common in creative writing: in the first and in the third person. Writing in the first person means that the narrator acts as the protagonist. Readers will see “I” in the text and will understand that we are talking about the main character.

The second person is rarely used when writing creative works, but rather used for instructions. For third-person, there are several variations. You have a limited third person, a plural third person, and an omniscient third person. The first is what you usually use.

The third-person narrator uses “he/she/they” when referring to the character you are following. They know the inner thoughts and feelings of this character. This is very similar to the first person, but instead of a character telling a story, a narrator takes his place. The third-person plural is the same as the limited, except that the narrator now knows the inner thoughts and feelings of several characters. The final, omniscient third person is when the narrator is still using “he/she/they” but has all the knowledge. They know everything about everyone.

While non-creative writing may have dialogue (for example, in an interview), this dialogue is not used in the same way as in creative writing. Creative writing requires dialogue to support the story. Your characters must interact with each other to advance the plot and develop each other more.

Mary Mitchell

Figurative Language

Part of what makes creative writing a piece of art is the way you choose to create the vision in your mind. This means that creative writing uses more anecdotes, metaphors, similes, turns of phrase, and other figurative expressions to paint a vivid image in the mind of the reader. It doesn’t matter which language is English or not.

Keep your writing sessions short. Writers—whether self-publishing or full-time publishers should give themselves writing assignments of no more than 40 minutes. The limited-time frame gives you the freedom not to fuss over your work and write on a creative impulse.

Emotional Appeal

Any letter can have an emotional appeal. However, this is the purpose of creative writing. Your job as a writer is to make people feel what you want by telling them a story. In this way, they can understand better the idea and enjoy your paperwork.

For students in need of targeted support, seeking thesis writing help is another practical solution. Writing a good thesis requires a lot of research, planning and structure – skills that can be hard to develop without guidance. By going to trusted professionals you get access to expertise that will make sure your arguments are well supported and your narrative flows. This frees up your energy to channel your creativity into other projects while delivering a polished and academically sound thesis. In the end, combining creativity with strategic support means you can achieve personal and professional success.

5 Tips for Writing More Creatively

From bloggers to creative writers of non-fiction books, everyone wants to find ways to creatively improve the writing process. No two great writers are exactly the same, but here are some writing tips that can inspire you to think creatively:

- Learn from the best, but don’t copy them. It is important to read famous authors as a demonstration of great writing examples and learn what they are capable of. Depending on your writing style, look for highlights of the genre. If you want to write literature for young people, look to some touchstones for young people, such as J. Rowling’s Harry Potter series, R. L. Stine’s Goosebumps universe, or Judy Bloom’s poignant coming-of-age novels. If you want to write science fiction, study the work of Isaac Asimov or Neil Gaiman. If you want to write fantasy novels, check out The Lord of the Rings trilogy by J.R.R. Tolkien. If you like horror, try H.P. Lovecraft and Stephen King. But do not confuse the ideas of these authors with your own. Use your favorite books as a starting point. To be truly creative, you must hone in on ideas, styles, and points of view that are unique to you.

- Create a character based on someone you know. Cinematographers Joel and Ethan Coen said they got the idea for The Big Lebowski’s plot when they created a badass detective thriller with a real-life friend as the detective. Many authors have used the traits of a best friend, family member, or colleague as part of a great plot idea. So the next time you’re around people you know well, jot down a few observations about their behavior—in your head, on a notepad, or on your phone—and see if it sparks some story ideas. A key supporting character or even the main character may be made up of people you know.

- Use the snowflake method to brainstorm. Created by author and writing instructor Randy Ingermanson, the Snowflake Method is a method for creating a novel from scratch, starting with a basic story summary and then adding additional elements. This works well for all kinds of creative writing. To start using the snowflake method, think of a general story idea and describe it in a short summary. The snowflake method then requires you to embed that sentence in a paragraph, using that paragraph to create various character descriptions. You then use those descriptions to create a series of storylines involving these characters, and each of these storylines goes back to the main idea behind your snowflake.

- Find an environment that encourages creative flow. When it comes to creative flow, the real life of a writer often follows a cycle of ups and downs. Once you hit a “boom” period, let ideas flow, and don’t give up. Writing workshops or even writing retreats often generate such creative bursts. They do this by sharing writing exercises designed to boost creativity and by providing a place where writers are surrounded by their peers. If you have never participated in intensive writing programs, consider this. Even an online creative writing course can offer valuable writing techniques for everything from character development to non-fiction storytelling to poetry writing.

- Try freewriting. This creative writing technique is the practice of writing without a prescribed structure, meaning no outline, cards, notes, or editorial oversight. In freewriting, the writer follows the impulses of his own mind, allowing thoughts and inspiration to come to him without prior consideration. Let your stream of consciousness inspire the words on the page. The first time you try to free-write, you may end up with useless material. But with writing practice, you can use your freewriting practice to perfect your technique and ultimately unleash your creativity.

Don’t ignore random ideas that come to your mind. Even bad ideas can inspire good ones, and you never know what will inspire a better idea later on. Keep a notepad or download a note-taking app to conveniently jot down or write down any content you can think of – it can come in handy in unexpected ways.

Effective Creative Writing

Everyone knows that creativity is not an easy task, because inspiration can come and go unexpectedly. When you are on a wave, then most likely the words themselves will fall on the paper, but it is important to understand in what order to structure them later and what to do when the inspiration passes. It will not be superfluous to read the tips:

- Develop your powers of observation by keeping a diary. Journaling is an effective way to increase your adjustment to the world around you. As you write in your journal, push yourself to describe the places you visit – who inhabit them, what they look like, what they smell like, and what kind of food, plant life, or architecture you see. Record dialogues you hear or conversations with people you meet. Getting to know how people talk and the topics they are interested in talking about will help both in writing creative dialogue. You will find yourself relying on this information as you set out to write the first draft of your paperwork or short story.

- Write after hours. Scheduling the time to write is important, but it’s also helpful to write during odd and spontaneous hours when your mind and mood are changed.

- Write when you feel uncomfortable. Believe it or not, authors might be encouraged to write when they are incredibly tired, busy, or even feverish. By allowing a new mental state into your process, you can review what you have done and see something with new potential.

- Capture your dreams. Allow yourself to daydream about your stories and take notes. Go for a walk, and then come home and write down any thoughts you have about the story: the characters, the details, the dialogue. If you repeat this action over several days, you will most likely end up with a disjointed sketch of the story.

- Go outside and move around. Leaving the house and getting moving—walking or jogging—has been a part of an expert’s writing process for years. Many writers have found that physical activity is a way to both activate new ideas and facilitate the creative processing that physicality and distance create.

- Make checklists of parts. When an idea for a story starts to seep into your mind, do some research. Think about the setting and motives for writing, and then make a checklist of the details you might want to include in your story.

- Be bold with the shape. The most important rule to remember in fiction is very simple: don’t be boring. Experimenting with form—surprising yourself and readers with structure—will pay off.

- Read as much as you can. It’s much harder to master creative writing if you don’t have links to draw on. Notable writers throughout history have produced great examples of well-written creative writing that any aspiring creative writer should read. Read famous works of great writers in a variety of genres to understand what interests you.

- Have a point of view. Fiction often has a story, message, or lesson to share. A narrative without a drive behind it will seem flat, and your audience won’t understand what your story is about or why they should care. Use your unique voice to tell a story that will resonate with your audience and connect with them in a way that makes a lasting impression.

- Use literary devices. Literary techniques help you write vividly and create imaginative scenes that are an integral part of good writing. Metaphors, similes, and other forms of speech create powerful imagery that can stimulate creativity and create vivid imagery. Alliterations, consonances, and assonance can improve the sound and rhythm of your words.

- Learn your audience. Is this story just for your creative writing classmates? Or are you an academic writer trying to enter the young adult writing market? It’s rare to find text that will appeal to all demographics, so knowing your audience can help you narrow down its tone and reach in a way that appeals to your target audience.

- Start writing. This is especially important for beginning writers. Many beginners may feel intimidated or confused about their creative work and where their imagination takes them. However, with freewriting, creative writing exercises, writing tips, and practice, you can improve your writing skills and become a better writer in no time.

- Accept a rewrite. A writer rarely ever gets it right in the first draft. You can have flexibility with your content, but don’t be afraid to cut things out, eliminate what doesn’t work, or, in some cases, start over completely. Storytelling and world-building take a lot of time and thought, and it’s only through rewriting that you can create the version that works best.

- Try a writing workshop. It introduces you to a community of writers who can help with your creative writing process by offering feedback and constructive criticism on various elements of your writing, such as the story, main characters, setting, and word choice. Whether you’re writing your first book or you’re an experienced writer suffering from writer’s block, writing groups can offer helpful suggestions or inspiration.

Note! No one will write a good paper if they do not follow the steps that the experts in their field have taken before. Therefore, you should not neglect these tips.

Now that you’ve read the tips, you can feel more confident about writing creative work when you realize that you’d like to do it. Inspiration is a fleeting thing, so it’s important to catch the moment in time.

Recommended reads

5 Forms of Creative Writing

Creative writing exists in many forms and is widely available to all kinds of writers. Some writers try their hand at writing as students in high school, while others join creative writing programs to earn certifications such as a Master of Fine Arts (MFA) degree.

- Writing fiction. With many genres and subgenres, both short stories and novels include a wide range of themes, styles, and details created by authors to create worlds that feel like real life. Writing fiction can give the writer a lot of freedom to create a creative original story populated by fictional characters that are related and three-dimensional.

- Creative writing of non-fiction. This genre includes various creative writing techniques and literary styles to convey truthful, non-fiction narratives. Creative non-fiction works such as memoirs and personal essays use more emotion and tend to emphasize plot and tone rather than the more traditional non-fiction subgenres.

- Scenario. The script weaves narrative into action blocks and dialogue text, creating entire scenes and often following a three-act structure to tell the story. Traditionally, screenplays were written exclusively for TV shows or movies, but the advent of new technologies and streaming devices has made many formats possible.

- Writing plays. Playwriting is a form of creative writing designed to be performed live on stage. Plays may be one or more acts, but due to space constraints, effects, and live performances, plays often must use creativity to properly tell a complete and compelling story.

- Writing poetry. Poetry is rhythmic prose that expresses ideas through music. It can be written or performed. It can be short or consist of several verses. It may not have a rhyming pattern, or it may be complex and repetitive. Poetry, like songwriting, is a versatile form of writing that allows the author to use cadence and meter to enhance their expressiveness.

Someone writes it for fun, and someone wants to write the next New York Times bestseller. Whatever the reason, there are many options you can use when it comes to creative writing, and you are free to choose any of them even if you need help from a creative writing service online.